Just to start: Could you please tell us about the beginning of your art career? You initially studied law and then literally did a 180 degree turn. Was it something specific that has inspired you to take an artistic path?

I had an unconventional start, moving from law to art. Art has always been a constant in my life, and I studied law for a university degree. Growing up in Lagos, Nigeria, I was drawn to the power of expression through visual arts and how it could relay things I didn’t quite have words for. Towards the end of secondary school, I had to decide what course to study in university. I had a passion for making and wanted to be an artist but had no idea where to start. My parents encouraged me to study a “professional course” so as to have a financially secure career path. So I applied for Law.

Throughout my university studies, I kept up with my art (painting and drawing mostly). I was restless to create. When I was done with university and Law School, I interned as a studio assistant with Peju Alatise who is a Nigerian artist I always admired. It changed everything for me. Her discipline and passion for her practice was infectious and it was then that I could truly envision life as an artist. My passion and desire to have an art career had intensified over the years. So after completing Law School, instead of applying for a job at a law firm, I applied to Art School for an MFA. I ended up attending Parsons School of Design and completed my MFA in 2018.

And here I am now.

© Layo Bright. Image: Rebecca Ou

You are a sculptor and visual artist, exploring the themes of inheritance, identity, colonialism, and gender. You also pay close attention to migration and border imperialism. This is a wide variety of complicated topics that co-exist in your works. Are they based on your past experiences and memories? Where do you find inspiration and what influences your creative thinking?

I’m concerned about a lot of issues that frame human existence and the ways we treat one another. Most of this is through my personal lens of what I’ve lived and seen, what friends and family have lived and seen, what history shows us of the past, and how it repeats itself often times in the present.

I’m inspired by our unique backgrounds, the current times we live in, the fragility of life, and the resilience to survive while navigating complex issues that seem to define us. There’s an extensive list of artists I’m influenced by, including Simone Leigh, Wangechi Mutu, Ebony G. Patterson, Sanford Biggers, etc.

I’m often drawing from cultural identity, textiles, materials and symbolism to question our present circumstances and where the current environmental and political tensions will lead to. Though I don’t attempt to draw a conclusive statement in my practice. So there’s a continuous thread of inquiry in my practice which involves figuration, abstraction, and assemblage.

You work with textiles, to be more precise, you use gele, a traditional Nigerian head tie, so your remarkable sculptures of female heads often wear gele of different colours and shapes. How did you come up with this idea? Could you describe the art “journey” you have undertaken to get to this point?

Gele is a type of headdress commonly worn in Western Africa on occasions (headdress in other parts of the continent go by varied names). I went through family albums, photos of women in my family, especially matriarchs: my mother, grandmother, great grandmother, great great grandmother. All wearing gele of different styles in these photographs. Which led me to think of the legacy that gets passed on through this tradition.

When I started making this body of work, they started as self portraits, with the gele textile incorporated directly in the work. Each gele has been worn by my mum to different events. She has danced in them, laughed in them, celebrated and mourned. So I think of them as a personal and collective archive, where she partook in different events that brought people in our community together.

With research, I encountered histories of headdress in the black diaspora. There’s a part of my process that involves endurance and resilience. In thinking of historical events and suppressive laws that sought to suppress black women e.g. the Tignon laws of 1786 which stated that women of colour must wear a tignon (a type of head covering) or scarf to cover up their hair.

© Layo Bright, Anacardium occidentalis (Epo cashew), 2019, Ghana-Must-Go bag, pottery, gele, pigment, wood, mixed media, 71 × 60 × 46cm / 28 × 23.5 × 18in. Image: Rebecca Ou

Your sculptures and installations address African narratives and often question issues surrounding the continent. To what extent do the current political and historical narratives influence your work?

Migration and perception are at the forefront of my mind when it comes to that. Migration is the story of humankind. It has always been pivotal to human existence, ever since the earliest homo sapiens migrated as a necessity for survival.

I am interested in exploring international migration as it exists today and what it has been like historically. We have witnessed gross injustice when it comes to migrants: from powerful countries adopting anti-immigration policies, to walls being put up and kids separated from their families, to governments turning a blind eye to the plight of migrants drowning at sea. It’s an issue that has shaped politics over the decades.

I work with materials that tie into a collective experience of migration with the Ghana must go bags I use in my works. They are checkered nylon tote bags that were imported from China to Nigeria in the 1980s. There was a xenophobic decree at the time that forcefully expelled around 2 million Ghanaians from the country. With the urgency of the situation and having to flee on short notice with personal belongings, many Ghanaian migrants used the bag to move their belongings. If you’ve ever used one of the bags you’d know that it’s cheap, sturdy, takes a lot of stuff in it and it’s lightweight. This whole event, of a mass exodus of Ghanaians fleeing with the bags, led to the bags being known as Ghana must go bag in Nigeria.

Similar histories have repeated in other parts of the world with this same material. It’s known as ‘Zimbabwe bag’ in South Africa due to similar xenophobic histories, in Germany it is called the "Türkenkoffer" (Turkish suitcase), in the USA, the "Chinatown tote", in Guyana, the "Guyanese Samsonite", and in various other places, the "Refugee Bag".

Speaking about your choice of materials, what are the key messages that you want to transmit with it? Do you explore femininity and traditional culture or should the gele be rather considered a metaphor for something else?

There’s different frequencies I’m interested in: from the self, to the social, to the political, to the cultural, to the spiritual, etc. I work with materials that I have encountered in a narrative quality. By ‘narrative quality’ I mean in the sense that there are histories they have been a part of, and that have shaped collective perception and identities. This is why I use specific materials like ‘gele’ and ‘Ghana must go bag’. I’m interested in their origins, the conversations they generate, and how they exist in the world now. They encompass a range of themes that include gender, identity, culture, fashion, class, migration, etc.

It’s not my intention to use metaphors in my work as a mode for deciphering what it’s about. I’m more interested in the questions that it brings up, rather than it being deciphered like a code. I generally enjoy experiencing art that leaves me thinking and asking questions.

© Layo Bright Studio. Image: Balazs Szeti

You have recently been selected for an art residency at NXTHVN, a New Haven-based arts incubator. Could you please tell us, what are you currently working on? Though some of your sculptures have been shown at Future Fair in NY, surely there is much more!

I’m enjoying exploring different aspects of my practice right now. The Fellowship at NXTHVN has afforded me the time and space to reflect on different bodies of work that I previously didn’t give enough time to. I have glass pieces I’m working on, as glass has become an important medium for my practice. I think of the properties of glass: how it can be reflective, transparent, opaque, and manipulated within figuration and abstraction. I am working on my sculptures as well. Sculpting is very intimate to me, a kind of choreography of my hands through gestures that results in portraits based on family members.

Let us talk about your recent exhibition “To Heal and Protect” presented by Welancora Gallery, Brooklyn, NY. What topics were you addressing with the artworks featured at the show?

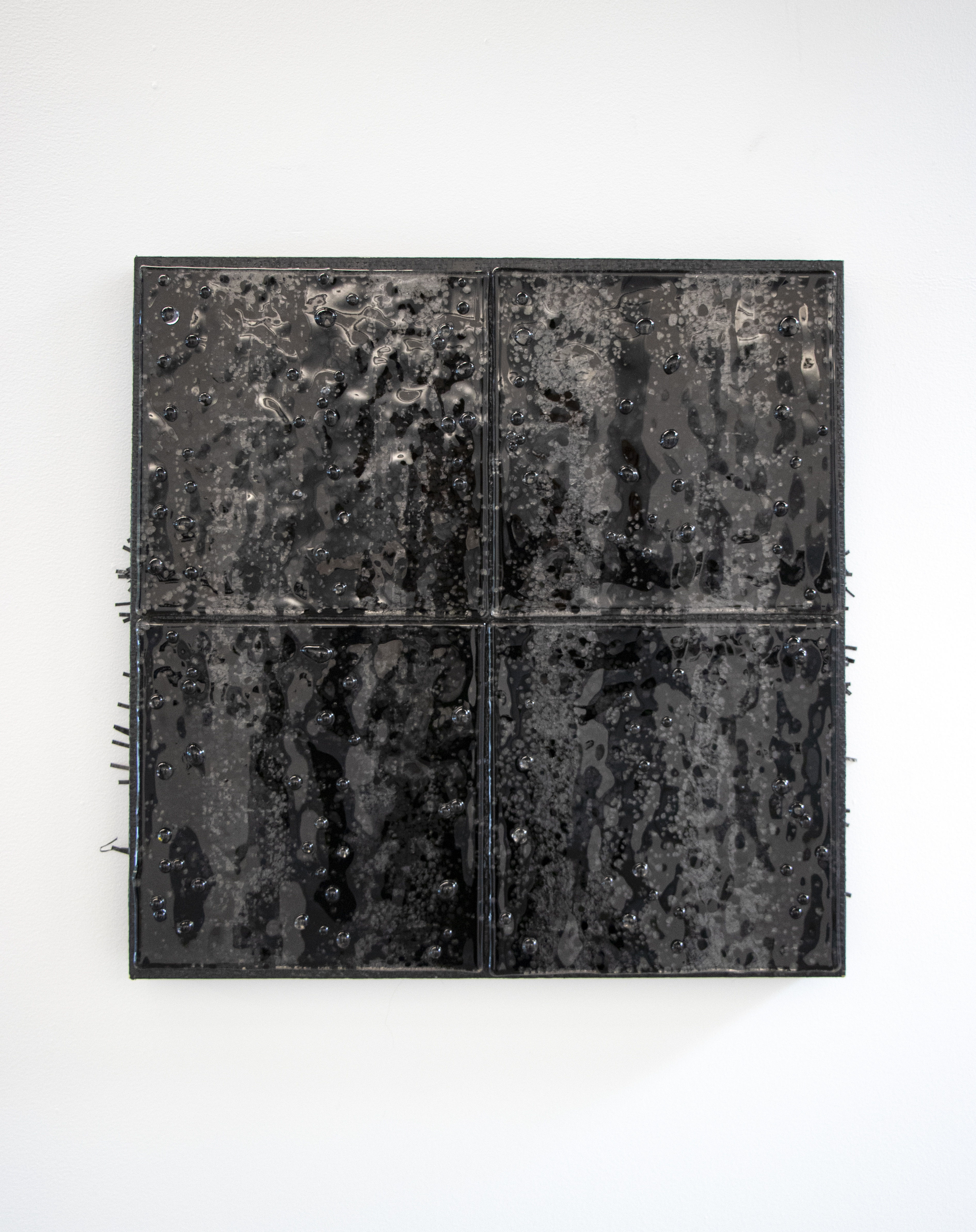

When Ivy Jones (Founder of Welancora Gallery) first told me about the exhibition, I was drawn to the theme of adornment as a gesture of healing and protection. It made me think of what we wear, cover ourselves with, and how we express a unique sense of self. And how my sculptures with the headdress were both adornment and protection, while having a regenerative environment around the figures with the leaves and wood. I also had a glass panel piece, “Dark Matter”, made of fused glass, Ghana must go bag, and wood. This piece focused on themes of migration, with the glass providing a lens through which to reexamine our proximity to it.

© Layo Bright, The Constant, 2021, Fused glass and Ghana must go bag on panel, 51 × 51 × 5cm / 20 × 20 × 2in. Image: Layo Bright

And now let’s throw a glance at the future. What is the most extraordinary project, you would like to bring into life one day?

A monumental glass sculpture! I occasionally dream of it. It has been the cause of sleepless nights and much restlessness over the past year. It would be incredible to have that happen someday!

And last but not least. I am curious to find out what do you think about all this big fuss around NFTs as an evolution of art. Do you believe that NFTs and digital art have the potential to disrupt the future of the art market?

It’s exciting to see artists have another medium and avenue of art making to explore with NFTs! It’s still early days and I don’t know if it’ll disrupt the future of the art market, though I do think it’s giving artists more range while generating conversations on resale rights. I’ve read about some of the auctions, which have generated a lot of interest from artists and collectors. I also know friends and colleagues who have been exploring it in their practice with some success.

Interview conducted by Valentina Plotnikova